A Few Ways Grad School Prepared Me For Writing Fiction

And a Few Ways it Really, Really F&$%#ing Didn't

I think I’ve mentioned before that I wrote my first big, serious attempt at long-form fiction in college (roughly 60,000 words). I spent my gap year writing abysmal horror stories and failing to start another novel.

By my first semester of grad school, I was writing about a guy who was trying to use Roland Barthes’s A Lover’s Discourse the way any normal person would use Neil Strauss’s The Game, all the while insisting to myself that it wasn’t a total rip-off of Jeffrey Eugenides’s The Marriage Plot.

This probably tells you everything you need to know about my Masters, or at least puts you off of investigating any further.

A recent chat about English degrees and MFAs over at TL;DR got me re-thinking about my scholastic pedigree… Also my friend Diane asked me about once and I never answered, so here it goes: How, exactly, did doing an English PhD prepare you for writing fiction?

This is a good, but hard question for me. I’ve always “been” a creative writer in the sense that I’ve always written creatively. I took as many courses as I could in college. Before grad school I worked very hard to learn the “business” of writing fiction (though with all the ambition of Daedalus, and even less of the foresight). And while I continued writing fiction in grad school, it definitely wasn’t out in front; even in college, it looked like my skills lay in the world of nonfiction prose, more so than storytelling. Still, some serious encouragement from my wife and friends kept me from giving up entirely—or, rather, they told me that they’d each take a turn at killing me if I ever abandoned the fantasy setting I’d been working on for years.

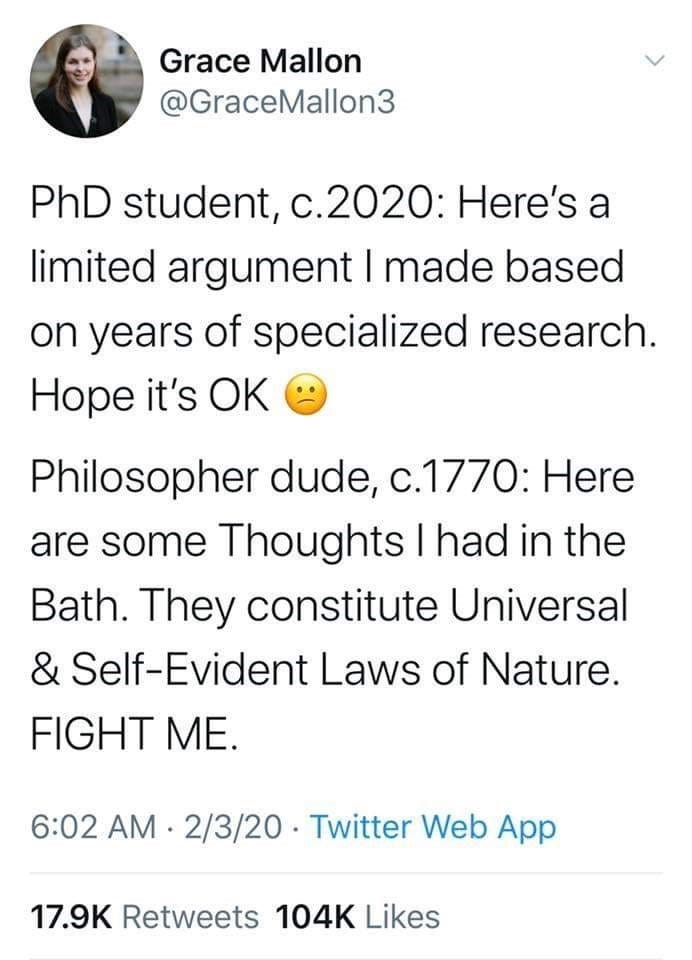

But there’s a reason why a PhD in English (Modern Literature and Culture track, with field specialties in the Catholic Imagination, Postmodernism and Literature “After Theory,” thank you very much) is very, very different from a Masters of Fine Arts.

But, as in all things, your mileage may vary. Mine sure did. And in any case, it’s not like I have a track record of publications to prove all this out—of my roughly four dozen publications since college, half a dozen would count as “creative writing” in the sense we mean it right now. Still, I think I’ve got a decent enough handle on the experience to explain how studying literature equipped me for writing fiction—if not for living.

How to Differentiate an MFA and a PhD in the Wild

So, first off, what these things are and are not:

An MFA is, more than anything, a “residency” program during which one reads, writes, and solicits feedback from a cohort and—more importantly—a professor. Course work is generally minimal in an MFA; in this sense, it follows a more “classical” or European model of education. You generally go in with a project in mind—a novel, story collection, or chapbook—and your completion of your project determines whether or not you get a degree. Meanwhile, your efforts are routinely judged by your colleagues in the program and by your professor. This last detail is the most important, and usually determines whether you consider your MFA to be “worth it.” Your professor is the subject matter expert as well as a mentor, learning your various capabilities as a writer and helping you prepare pieces for publication. If you are someone who requires more structure and guidance, having such a presence can take almost all the sting out of your first forays into submission and rejection. But if it looks like the professor is the only thing setting an MFA apart from, I dunno, what you already do during your free time already, then… Let’s just say there may be better ways to spend a hundred grand.

Now, let me be clear, this is not going to be a ringing endorsement of a more traditional grad school experience over an MFA. It took me two of my five years in my PhD to recoup the cost of my MA. That said:

A PhD in English is a terminal degree in the scholarship of arts and letters, not in the creative process itself. One takes courses in various specialized topics, all the while earning their keep by teaching introductory literature and writing courses and doing other academic “service” (for which one is paid—it’s not much, but stipends are standard). Usually around year three, you establish a handful of related fields in which to distinguish yourself as an expert, taking a year “off” to read roughly 100 works representative of your fields. At the end of your reading period, you are rigorously tested (a written and oral process that takes about a week) and, should you pass, you are then given the “privilege” of taking 1-2 years (or way the hell more) to write a book-length piece of original research that can serve as the first keystone in your career as a literature professor…except the species is pretty much extinct.

Okay, so we all know I did the latter, but… we were originally talking about creative writing… Right?

I Read All the Things

My PhD in English prepared me to write fiction primarily because it had me reading all the damn time.

Now, it also meant I DNF’d a lot of books, because I mostly needed to talk about things at a round table and write papers. I didn’t necessarily need to have read things cover-to-cover to do this; paying attention in class often taught me where the important passages where, and I could write my papers based on “torque” alone.

On the other hand, DNF-ing a book you’re not wild about might be considered a good habit to some. It certainly taught me the value of my time, and to not waste it on things I wasn’t enjoying. But more importantly, the sheer amount of intensive, attentive reading I did can only be counted as a good thing.

A word of warning though: a little less than a year out from earning my degree, I—more than anything—wish I’d paced myself better during my intensive study. The perception of work-versus-play affects more than you think, and when I started viewing reading as “work,” I taught my grey-matter reward systems to stop firing and making me feel good at the end of a long stretch of 100+ pages. When you’re not training your brain to anticipate delayed gratification, to slowly drip dopamine over a long reading session, food and screens start looking mighty attractive whenever you need a break and… Well, welcome to the 21st Century.

At the same time, though…

I Destroyed Distraction

Academic work taught me the need for removing distractions in order to do the deep work I wanted to do. Motivation wasn’t always enough; I’m a “rollercoaster” type of person, in that I require some significant and excruciating wind-up to get me over that big first hill, but once I’ve done that I can make three circuits around the track in record time after plummeting into a fever of deep attention.

Still, that first hill is excruciating, and I’ve discovered I need different habits and technologies in order to clear the bump. I use different apps to box myself in and knuckle down when it’s time to do deep work and, once I’m there, it usually doesn’t take long for me to stop being intimidated by a problem and start tackling it—you know, something like writing a novel outline, or untangling the deleterious ontology of energeia that has spelled the literal death of Western civilizations for millennia. Par for the course.

Obligatory caveat? Habits only stay habits if you…habituate. I’ve fallen off the horse a thousand time, but with a 90,000 word dissertation and a 90,000 word novel under my belt, both written within a year of each other, I’ve at least proven to myself it’s possible to do that kind of work, and sometimes that even helps me to get back to it.

I Got Used to Figuring it Out

I think most graduate students start off trying to show how smart they are (Not speaking from experience of course, ha ha HA). They practice jargon in their first papers, believing that if they can use enough of it then their relatively shallow insights (whether or not they’re recognized as such) will pass off as genuine hard work. I discovered pretty quickly, however, that the problems I encountered in literary criticism and the philosophies informing it were genuine questions I wanted to answer to (like the aforementioned ontology of energeia which I do not promise to stop bringing up). I wanted to know how far I agreed with these various perspectives, and where my points of departure signaled something deeper than mere distaste. This required actually figuring things out, sitting with many, many (many many many) different books and articles and lines of argument in order to figure out what was really at issue, how others had “solved” that issue and how I might be poised to do the same.

Translating this propensity for exhaustive research into skills for fiction has been a little difficult. Much more of the “writing advice” world is filled with noise that’s better filtered out than exhaustively researched and distilled down into a plan of application—though if you can ever come up with the latter, and it keeps you from ever losing a full week to googling writing advice ever again, then do it. On the other hand, when I apply the same diligence to my actual work, then things get interesting: I ask more comprehensive questions of my stories, and the precise craft-y problems I encounter become more salient. I’m motivated to not only solve a problem in a piece, but to solve it in a way that teaches me more about the nature of the problem itself and how to address it again down the road. In these ways, the writing of fiction is mercifully more metaphysical than is real life.

I Learned to Translate

This is probably the most important thing on the list. As a teacher, I learned that you never really know how much you do and don’t know about a topic until you try and explain it to someone else. This was where the rubber really met the road for me, and I realized the worst feedback I could ever receive in any situation ever was, I don’t get it.

Like, let me stress again: these are high stakes for me. I genuinely believe that the historical problems of philosophy and theology are relevant to everyone everywhere at all times, and that literature calibrates and elucidates the ways in which these questions hold our lives at stake all the time, everywhere. It absolutely kills me when I can’t adequately externalize those values. I will forever I remember sitting next to one of my former students, asking him what he thought about some of the content in this newsletter, and hearing him say, “I don’t always understand what you’re talking about, but I love seeing how you’re doing.”

It guts me. I want to be intelligible. I want the stakes to translate.

This means that, where possible, I learn new words for my already jargon-laden vocabulary. I have to learn new illustrations for things, and that means really knowing the material backward and forward. I have to think about my word choices, and the feelings that individual words invoke—how they might connect in the minds of other people in ways that usually escape me. Believing I hold a unique perspective on what’s at stake in the world has thoroughly motivated me to stop thinking about my own satisfaction with my logic or my style and to give all my energy to manifesting it for a reader. And on this one point, the difference between story and argument completely collapses, as far as I’m concerned.

… And For Good Measure Here’s One Big Way None of It Did Me Any Favors At All

While doing my PhD, I had several friends of mine—MFA holders and students alike—tell me they wished they’d gone the PhD route instead. To them, looking back, they saw the intense reading and study required by a PhD as much more valuable, capable of paying much higher writing-related dividends, if over a longer period of time. (Dammit, I hope they’re right, but being patient is hard.) And that by itself supplanted the fact that they had to pay through the nose for a space in which to work really hard, without also receiving a reasonable time-to-degree that allowed them to supplement their practice with much-needed study.

I’ve learned to really value this perspective, and the more I trust the process the more I appreciate the wider-ranging applications of my degree. However, pivoting into those applications isn’t easy—in fact, it’s a sticky set of brakes on everything I’ve been saying so far.

Because when doing a research-based degree, you write a lot and learn to write very well… But you’re usually doing one kind of writing that takes more brain power than you have to spare most days. The rigorous, disciplined nature of scholarly writing sets you up to work logically, at everything, almost to a fault—usually at the same time as you’re throwing logic out the window due to an existential crisis over the sand-castle fragility of human knowledge.

So, my argumentative channels are cut real dang deep. To this day, I can write thousands of words of nonfiction or highly specialized prose in a very short amount of time and pick right back up where I left off after the Benadryl wears off.

In the time it takes me to write 10,000 words of nonfiction prose, I manage to write maybe 4000 words of fiction.

Now, I’d still call both of these creative work. Scholarship is endlessly creative, an effort at genuine imagination. But in this realm, you’re synthesizing based on prior expertise, not necessarily letting your creative brain go to town. It makes your generative process a lot more rigid.

On top of that—and this is the real point I want to make here—all your work has a “point,” all the time, and after doing so much work with a “point,” the idea of “playing around” is foreign to me now. So much of my skill acquisition has focused on producing, not on practicing. The nearest I got to “play” was a literal library of notes that never made it into my dissertation. I’ve written many, many pages that will never see the light of day as I tried to understand something better—but all those pages where still instructive attempts at penetrating the thick skin of a problem I wanted to solve. This “playful” process does not—at least for me—easily translate into fiction, especially not into the fevered flights of lucid imagination some of my friends describe. My mind has not yet remembered how to kick back and relax in that way without worrying about whether or not it’s “doing it right.”

In many ways, I think it all goes back to the motive and the stakes. Academia is persuasive through rigorous logic; rarely does it lean on the pathos and the ethos that make fiction and even creative nonfiction impactful. It teaches you how to notice and talk about those things, but not how to do them in the same way yourself.

As a result, I am very good at pointing out what’s working in a story. Maybe uncommonly good. I can say why certain elements exist, speak to the motives behind their inclusion, I can imagine branching paths—what might or might not happen if something were added or taken away—and the implications of themes as they interact with one another. But I’m just starting to realize that all this insight came at the expense of a craftsman mindset. If I were an anatomist, I would be very good at the fleshy bits, but have almost entirely intuitive—and therefore limited—knowledge of skeletal structure. It only recently occurred to me that I could move muscle and organs aside and take a look at what’s beneath, and what I’ve found there baffles me to no end, unlike people who started working on their craft from the inside out.

… Okay, right, we’re still talking about fiction and not body disposal. ‘Hem.

In any case, that’s it for this one. It’s been good to take a look back at where I come from and what I’m trying to do now, and I hope at least some of this has been enlightening for you, too. I’ll say one more time—for myself as much as for you—that I’m choosing to believe, along with my MFA folks who encouraged me, that my “reverse excavation” of the art of fiction will pay off in the long run.

But it’s certainly a lot harder than I thought.