A while ago, Rick Wiles—one of the many faces of Big Christian TV—made headlines by declaring that vegan “meat” spelled the end of humanity as we know it:

They want to change human DNA so that you can’t be born again. That’s where they’re going with this, to change the DNA of humans so it will be impossible for a human to be born again. They want to create a race of soulless creatures on this planet.

We laugh, but Wiles is still—in his own, perverse way—asking a perennial question that only becomes more pertinent every year: what exactly does it mean to be human?

Literature loves this question, but speculative fiction treats it with special interest, urgency, and—well, speculation. What does it mean to treat humanity as a “limit” that we can push? Asking such questions forces us to struggle with defining the “human” in the first place. In his famous novella, At the Mountains of Madness, H. P. Lovecraft presented us with the idea that “being human” might refer more to capacity and moral responsibility more than to any kind of biological form (Lovecraft insists on referring to the alien Elder Things as “men”). Comic books, too, famously took up the question throughout the mid-to-late 20th Century, and it now firmly rests in the modern consciousness that being “human” has very little to do with genes, but with something else.

If we’re especially sappy, we might say it lives in the capacity to love.

Rory Power’s young adult novel Wilder Girls (2019) sits uneasily in this tradition, far nearer to Lovecraft than to the X-Men. Featuring a plague that mutates the bodies of the young girls it infects, Wilder Girls treads the well-worn path of what it means to be human, and where we touch the question’s limits. It also offers some familiar meditations on love being the answer, but the novel’s attentive focus on queer love puts these questions into new relief.

This newsletter started as a study in all the subtle little things I think this novel has to teach us in our present moment of pandemics, protests, and political exhaustion. But as I worked on it, I realized how little evidence I had for my points—at least, I had just enough evidence from the novel itself to think the thoughts I was thinking, but not enough to “follow through” on them in the ways I wanted. So I came to a different conclusion: the fact that those lessons lie in largely underutilized elements of the novel is, I think, something worth talking about.

Welcome to Raxter Island

Wilder Girls focuses on the Raxter School for Girls, under quarantine since a mysterious disease called the Tox started devastating the faculty and students at the school and, presumably, the wider world outside. Certainly, the wildlife has transformed around them, as the irises and the crabs become an alien blue and turn black when they die. Survivors of the Tox don’t escape unscathed, either, and the girls are menaced on all sides by foxes, deer, and even bears that have been zombified and made highly aggressive by the disease. The girls’ survival, too, appears to entail drastic mutations: second spines, scales covering arms, stony pustules where eyes used to be—and those are the tame ones. For some, such survival proves little more than a postponement, as their bodies slowly fail under the strain of their mutations—that is, if starvation or bears don’t get them first.

In the midst of all this, Hetty, Byatt and Reese (the former two being our narrators) have managed to create an island of affection and stability based around one another. If they can’t count on anyone else, they can count on each other—and that’s even when they take Reese’s violent outbursts into account. But when Hetty is selected to replace another girl on Boat Shift — a supply-gathering duty that briefly exempts the chosen from quarantine — her relationship with Reese is strained to the breaking point. Reese, you see, wants a chance to look beyond the walls for her father, who disappeared during the first wave of the Tox. Despite this tension with Reese, Hetty ultimately accepts the position, only to discover that she’s become privy to secrets that place she and her friends in mortal danger. When Byatt’s mutations produce a particularly bad episode and she disappears soon after, Hetty and Reese are forced to act on the little they know — which is already far too much — and find their friend before their small, fragile world collapses around them under the weight of secrets, betrayal, and raw desperation.

And it doesn’t help that they’re falling in love as they go.

Art above by Laya Rose

Rivalry and “Indifference”

From the outset, Wilder Girls makes competition into one of its major themes; almost before anything else happens, Hetty and Reese get into a violent altercation over food. Boat Shift is a highly-contested position among the girls, who form their own cliques and hierarchies despite what many of us would see as an obvious need to band together. This focus on competition despite a need for solidarity opens the novel up to a form of reading I’ve talked about before: an analysis of mimetic desire. When we read this way, the novel’s small lessons about love and community become much more interesting.

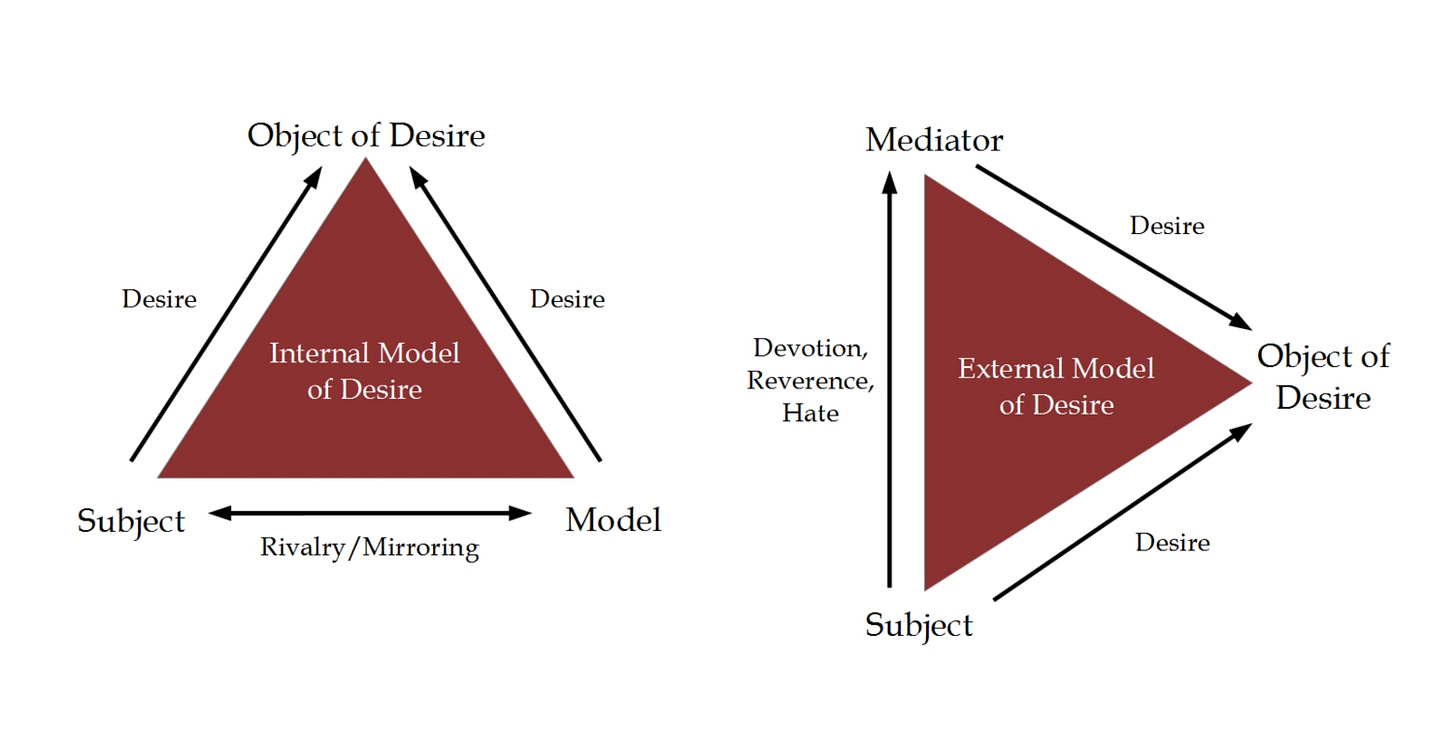

If you aren’t familiar with Rene Girard’s mimetic theory of desire, you can read my woefully inadequate post from way back when. Here’s a summary, though: desire is not spontaneous; it is learned. Desire always involves a desiring subject, an object of desire, and a model from whom the subject learns their desire in the first place. Sometimes, that model exists at a distance—being a sort of mentor, or source of admiration as the subject pursues their desires. However, if that model exists in a nearer orbit to the subject, they suddenly become a competitor:

The musical Hamilton offers some great examples: Alexander Hamilton looks up to Aaron Burr and wants to be like him. Hamilton creates an internal model of Burr, mirroring his actions—learning to “talk less; smile more”—in order to become a great politician. Meanwhile, as Hamilton skyrockets to prominence, Burr begins to see Hamilton as an external rival: someone who is standing in the way of his own ambition to be “in the room where it happens.” Thus, while Hamilton mirrors Burr in pursuit of personal fulfillment, Burr’s own desires become so wrapped up in Hamilton as his rival and mediator that he frequently loses sight of his own ambitions, instead becoming mired in a complicated mixture of hatred for and reverence toward Hamilton that ultimately sabotages Burr’s own designs and has fatal consequences for Hamilton.

This sort of rivalry can occur any time scarcity arises—even if its a perceived scarcity of power and prestige as in the above example, though ultimately those characters must reckon with their blindness to the opportunities in front of them (“The World Was Wide Enough”). The girls at Raxter, though, face a really genuine scarcity of food and shelter, making their rivalries that much more intense. It is therefore unsurprising to see Wilder Girls following somewhat in the tradition of Lord of the Flies, which remains a compelling narrative whose core motifs get repeated endlessly in popular fiction—especially post-apocalyptic—because of the way it handles rivalry and scarcity.

Yet Wilder Girls softens these circumstances—for better or worse—by demonstrating that the girls manage to find at least some peace in one another. We see several romantic relationships showcased in the novel, the majority being of lesbian orientation. On the one hand, such affection reminds us that the human capacity for love always finds a way to express itself even in dire circumstances. On the other, love in the context of desperation can become, as Sherlock famously says, “a vicious motivator.”

Girard doesn’t miss the fact that love itself can present as its own kind of “scarcity.” The “love triangle” is, after all, the quintessential paradigm of mimetic rivalry. In extreme cases, the competition over the beloved may become so fierce that the two desiring subjects start to care only about their rivalry with one another. As resentment and projection set in, a process of mirroring and indifferentiation takes place, where each competitor finds their whole identity wrapped up in the other person.

If this process proceeds unchecked, the subject starts to resemble their rival more and more in their toxic behavior. At that point, it is no longer even enough to win over the beloved, who has been reduced to an object: the competitor must also die, or else the beloved must be removed from the playing field, the quintessential trope of, “If I can’t have her, then no one can.” (If you want some really grisly examples of how this works in fiction you can’t do better than Junji Ito’s manga series, Tomie.)

Now, none of the events in Wilder Girls come to this kind of crisis. But as Hetty and Reese get closer to one another, we do still see glimpses of mimetic desire rearing its head. While this drama between the leading characters is ultimately subdued in favor of more physical and clandestine dangers, I think it’s still worth looking at some of these dynamics because they show off the real promise of Power’s novel—while also explaining the frustrations of many readers.

Love’s Fertile, Ugly Soil

Our first example of mimetic romance in Wilder Girls is a subtle one—seemingly innocuous, but telling nonetheless. In one scene, Hetty—who is becoming increasingly attracted to the hot-blooded Reese—admires Reese’s hair. She imagines what it would be like to have Reese’s hair, to be as beautiful as she is. She is, in other words, tempted to imagine herself as Reese; to lose her identity in the one she is starting to love.

From this scene, we can see that Hetty, to some extent, is a “mimetically minded” narrator in the terms laid out above. (Byatt may, indeed, be more so, but her arc alone deserves at least as much space as I can spare here.) Though in large part subconscious, Hetty is still very concerned with her position and stability inside the Raxter hierarchy. While she is affectionate with and fiercely loyal to Reese and Byatt, her affection borders on possessiveness in several scenes. When it comes to the Tox, Hetty is also concerned with her own shifting relation to the island; she fears becoming “of Raxter,” in the same ways the crabs and the irises seem to be becoming part of the island itself. Afraid of losing herself to the Tox—of becoming “indifferent” from the island—Hetty’s assertiveness paradoxically makes her vulnerable to making selfish choices, and many times the consequences of these choices are used to drive the plot forward.

Reese, meanwhile, surprises us despite her seemingly gruff exterior. The way she fights the other girls for food, we might expect her to be the most mimetic of all our named characters. In fact, Reese’s coldness and lack of affection belie a capacity for love and affection that is much wider than Hetty’s. We see glimmers of this in the way she talks about her family, and her willingness to invite others into her home. She suffers deep trauma due to not knowing where her father disappeared to, and the other characters don’t blame her, saying “she was most herself in her father’s house.”

The closer we look at Reese, the more we see that she finds her identity in other people: her father is her first major differentiator, and she finds profound worth in the father-daughter relationship. The love she learns from her family makes her world wide enough to receive Hetty and Byatt into it on their own terms, and enables her to take Hetty as a lover. The old saying goes that “you must lose yourself to find yourself,” and from a Girardian perspective this is perhaps the truest lesson you can ever learn. In Wilder Girls, Reese exhibits this sort of character in surprising and unexpected ways.

When Hetty returns Reese’s love, however, it is with a negative mimetic streak that comes to a head when the two of them do, in fact, find Reese’s father overtaken by the Tox. In a grisly, drawn-out scene, Hetty gets up-close and personal with Reese’s mutated father and disembowels him as Reese begs her to stop. Though Hetty may have been in the right, considering their own survival was on the line, her response to her own actions makes it clear that her heart is not as wide as Reese’s. While Reese mourns that their survival had to come at the expense of the father she loved, and she demands time to grieve, Hetty can’t understand how their being put in danger doesn’t cancel out Reese’s affection for her father—by now a mere memory—or her need to grieve in the aftermath.

Reese’s response—“We don’t get to choose what hurts us”—invites an important comparison between these two young women. Reese cannot choose what hurts her precisely because her capacity for love is so wide; she is able to appreciate things for their singularity, for their “mereness.” Hetty, meanwhile, believes she can limit pain by choosing those things she keeps close and keeping the rest out. Ironically, the tighter she holds on to Reese and Byatt, the more vulnerable she becomes to the pain of a mimetic relationship with those she calls her friends. While Reese’s patience and loyalty buoy her up in the end, Hetty never completely lets go of the perception that she is the “center” holding the three of them together.

Art above by dri

What Hurts Doesn’t Hurt Enough

I’m pretty sure anyone else who’s read the novel might have trouble recognizing the dynamics I’m talking about, but that’s part of my point: while these mimetic dynamics are present—and I think they are the most interesting parts of the novel—they aren’t allowed to play out in really satisfying ways for the characters. Hetty suffers consequences for her actions, but none of them are the direct results of the selfishness we see lurking under the surface throughout the story. And while Reese reminds us of the importance of grief, of remaining human and tenderhearted even under such dire circumstances, she never quite gets to demonstrate the heroism so potent within her character.

The result is a fantastic amount of tension between these characters that never quite gets to bubble over and be the true conflict or consequence of the story. You catch glimmers of this reading reviews of the novel, as the negative ones generally comment on the “one-dimensionality” of the characters, the lack of connection between actions and consequences, and the missed opportunities at deeper allegory and symbolism. Many also comment on the thinness of a romance which never quite revisits its major source of strain: what I am here calling the threat of indifference lurking in its heart.

Maybe you’ve picked up on the ways I’m using “difference” and “indifference” and gotten a little suspicious. In fact, Girard’s theories have not escaped unscathed for their privileging of the heteronormative. In a few places, Girard suggests that queer relationships inevitably face the breakdowns of rivalry and indifferentiation because they introduce too many similarities and sources of rivalry between people in relationships.

In one sense, it helps to remember that Girard is offering an anthropology, not making a moral judgment against the all-encompassing reality of mimetic desire, and he outright says that homophobia is reprehensible. Still, the problem remains that mimetic desire tends to roll over into rivalry, rivalry into indifferentiation, and indifferentiation into violence, and it’s hard to get around his insinuation that homosexual relationships are uniquely vulnerable to this kind of slippery slope.

And yet, some members of the queer community have found the lion’s share of Girard’s thought to be immensely useful. It’s also interesting that Wilder Girls seems not only aware of but accepting of this dynamic as Girard describes it. It is, of course, no accident that the comparison Hetty makes between Reese and herself is a comparison you’d be hard-pressed to find between straight couples. At some level, Wilder Girls encounters the difficulties of indifferentiation described above, and seems to suggest that it is a genuine and unique burden on queer romance, a problem for love to solve if it is to prove itself. Seen in this light, Wilder Girls is at its best when it’s exploring the threshold of humanity and seeking, along that threshold, new means of differentiation that can widen our perspectives on love and, in the process, allow more pluriform expression of love to take root.

The problem is that the novel doesn’t spend a lot of time doing this, and when it does, it misses some really key opportunities—one of them staring us in the face within the first dozen pages. If we’re willing to follow Girard’s logic a little further down this path, admitting that we need a source of difference to symbolically enable peace, order and love, then the Tox itself starts to emerge as a shadowy “hero” of Wilder Girls.

Art by Fujixia

A Tox Upon Us

The Tox, so say the girls, “gives us the bodies we need to survive.” From this moment, we expect it to play a larger role in the individual lives of the girls than it ever really does; when it appears in a scene, it brings far more pain than new potential for survival. From the Girardian perspective I’ve taken here, the Tox possesses a lot of underutilized symbolic and dramatic potential to convincingly push love into places that many still consider to be “improper” or “forbidden”.

Of course, many novels fail to “realize their potential”; if the reception of Wilder Girls has seemed especially lukewarm, I’d say it’s because of how very much the novel does well alongside those crucial areas that go underdeveloped. Power presents the Tox—with striking and beautiful prose—as an ambivalent force in the world: it strips the humanity from those it infects, but it also gives something back. Under its influence, Hetty and Reese demonstrate especial patience with one another and a capacity to forgive, even as they conflict over their own ideas about the limits and capacities of love. The novel does not allow us to imagine what might or might not have transpired between them without the Tox; we can only see their relationship from inside it, and see that their affection isn’t destroyed by their mutual affliction. If we’re willing to read Girard into this scenario, we have to grant that the Tox, in this case, introduces a series of differences that make new expressions of love possible. Unfortunately, we don’t get to see them develop in all the ways we might crave.

Of course, me being me, I can’t help but also see the quasi-religious potential here that may have added even more depth to the story. Playing both villain and hero in what can only be described as an act of God, there is an “ambivalence” to the Tox—a capacity to bring great peace and meaning at the same time as inciting violence and suffering. Scholars like Girard refer to this as the “ambivalence of the sacred”: the paradoxical capacity for belief in religion or the supernatural to have profoundly evil effects as well as overwhelmingly good ones, or for supernatural forces like God to be seen as the source and author of evil just as much as they are for good.

This is not to say that the Tox somehow achieves the status of a “god” in this novel, but I’m not not saying that either. If anything, the strange role of the Tox reminds us that, even now, such questions are never far from our minds whenever we are talking about the human capacity to love.

After all, don’t we all want to believe that love is—for lack of a better word—sacred? In the end, perhaps there really is no better word…