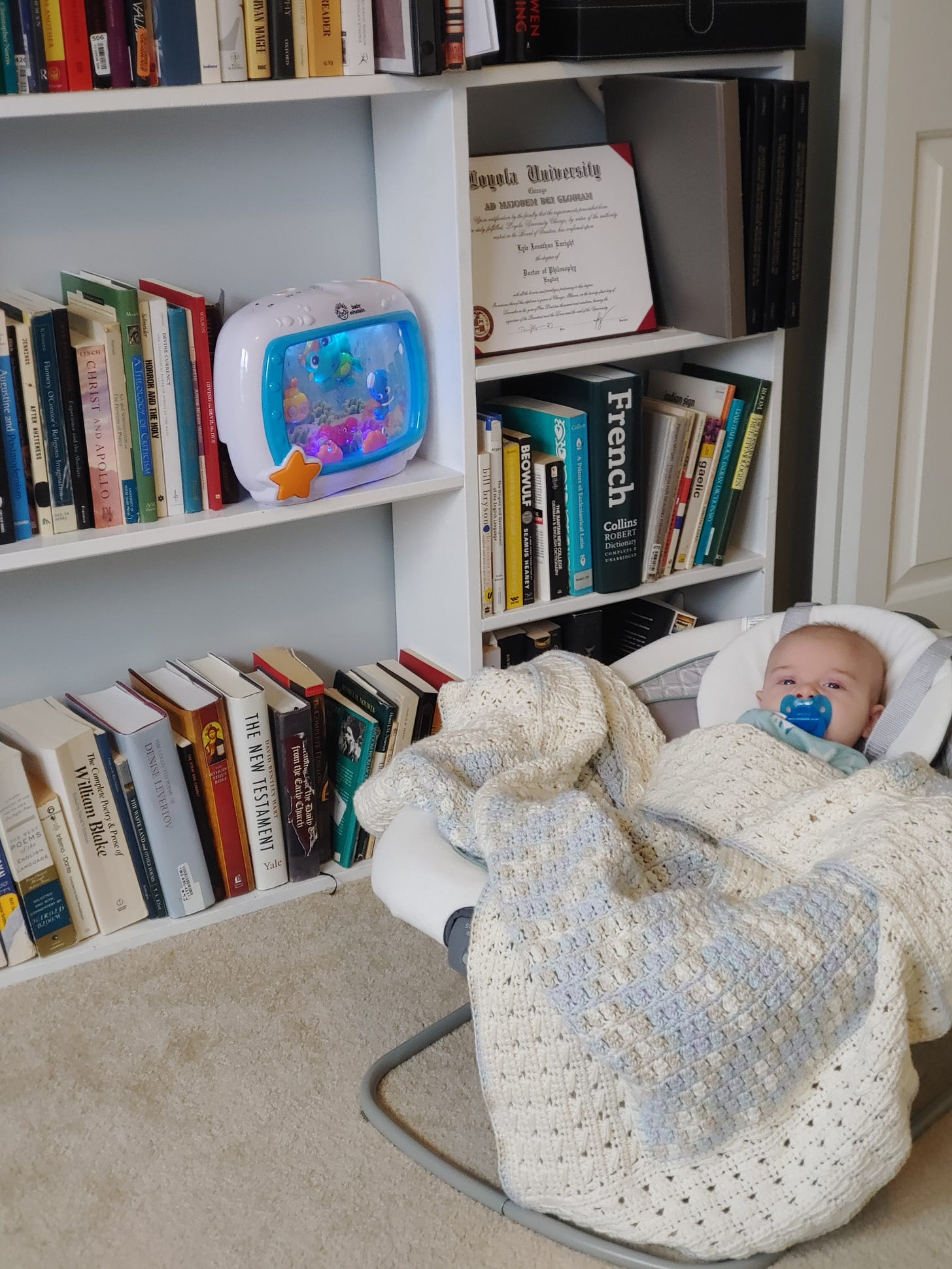

For everyone who hasn’t gotten the chance yet, meet Rowan.

He’s nine weeks old, fat and long, highly opinionated and already standing with all the poise of a tweaky linebacker. I hope he sufficiently explains my radio silence for the last… 5 months.

Well, I guess he explains a part, but not all of it. Maybe 60%.

I’ll try and fill in the other 40.

Yearning, Knives, and Newsletters

My average newsletter over the past 12 months was 3000 words long and, when I reflect on that, I have to make some assumptions.

Between preparing for a kid, and writing lots of other things (see below), doing this newsletter has, again, started feeling like a chore. The work of coming up with a “topic” I could write on for 2500+ words was daunting, my grad school days long behind me. Nowadays, I just don’t have those kinds of words to spare when I’m stealing daily time for book-length projects I hope will be vastly more entertaining. So I let this thing languish again, shaming me, afraid of of this thing I didn’t know what to do with.

About the same time, I learned the first big lesson of fatherhood: it’s always more efficient to confront your feelings. No one has time for you to have big feels and not understand them. Understanding, quickly and practically, becomes a survival mechanism.

So I tried to understand—quickly and practically—why I’d set such absurd expectations on myself in the first place, and grown afraid of this newsletter. Why, for instance, I’ve stopped telling people about me and underestimating the human element in all the things I try to say. Or why I’ve twice now defaulted to what I know best: academic essays and deep-dive research into things (only) I care about (at least in the specific way I care about them).

Nobody—least of all me—really has time to fish for the value in such a large pond

So: what—and how—might I do differently? How might I shrink the pond?

Now what?

With the new school year well underway, I’m missing the classroom and reflecting on what I wanted out of this experiment in the first place. I said it was “for my students” when I first started, but I’m not sure how well I’ve stuck to that vision so far.

If this were a real classroom setting, I’d hope for different outcomes. I wouldn’t be the one doing the research, for one. I’d be after wonder before I was after understanding, and understanding before I was after expertise in anything. With COVID still in the air, and major fear about what’s on the horizon, I want to try and come back to those roots and capture, in this newsletter/blog/whatever, what made my classes good when I taught at Loyola.

Good courses—any good things, really—add regular value to people’s lives. Ideally, I add that value at a tenth of the effort I’m tempted to spend just demonstrating expertise. My friend Anne insists that one of the most difficult things a scholar can do is make their knives “short and sharp.” By this, I take her to mean that one’s intellectual life is most meaningful to others when it is clear, targeted, well-aimed…and, of course, short.

Since my efforts tend to imitate something nearer a cumbersome, weighted net, this is a good chance to try and practice the other half of this advice: that yearning, love, desire is the best stone on which to sharpen one’s knives to make them short and sharp.

And I’ll tell you, if there’s anything fatherhood has brought into my life, it’s intense, lucid, often complicated love.

My new “Classroom” experiment

I’ve never been a very structured thinker, but that’s had to change in the last 2 months. Fatherhood has me thinking constantly about teaching again: how can I tame my chaotic intellectual life to provide moments of clarity and curiosity to my son? Such things don’t come naturally. They demand a strategy—and the patience to not, as I so often try to do, say everything at once.

Practically, this means that everything I do has an outline anymore, and I’ve found that the seemingly limiting practice actually pays off for both me and my readers. In a teaching spirit, I decided to think back a bit and outline an ideal moment in the classroom. If I could go back to my professor days, what would I hope would happen on an average day? Hell, how do I imagine an idea conversation with my son when he’s my students’ age?

Here’s what I came up with:

1. I’d open with a story. Something from my own life, hopefully connected to something from yours—the headlines, the current events we share. We live in the same world, and should start from there.

2. Our shared stories should connect back to a scene we’ve watched, or passages we’ve read that resonate with where life is at right now. Of course if it’s just me writing here, I’m responsible for watching/reading like a writer and a teacher, and watching/reading interesting things that you actually want to hear and think about.

3. The crafty bit. This is where we’d talk about how a piece is made—why it works or doesn’t, why we like it or don’t, why we understand it or don’t. How a thing is made impacts how we interact with it, why we find it interesting. The better or worse a thing is made, I think, the bigger thoughts it tends to provoke—but also the more practical things it teaches us about our own ways of thinking and making things. We practice the patience of looking at something very slow and close.

4. The “big thought” bit. This is where I’d start talking about the stuff I can’t leave alone, the part where we unpack how what’s going on in our reading or viewing links into broader traditions of urgent ideas. This is where I’d wax Foucauldian about the asylum in Dracula, or about how Nalo Hopkinson subtly normalizes non-nuclear relationships in her short stories and why that matters. This is where I’d rant about how I’m bored to death by religion in Brandon Sanderson’s The Way of Kings, because God is not just a really big object in the universe. It’d be visceral, fun, exciting, as my momentum threatened to derail us—but we'd reign it back. We'd have a point. It'd be short and sharp.

5. And this is where I’d promise that the points add up. I’d close with a "point of sail" that intimates how we’ll expand on these thoughts next time, that we’re following a trajectory that will pay for itself. I would remind you of the value of the “lukewarm take”, and I’d give you something to look forward to. Eventually, one day long down the line, I will have told you all I know. We’ll both be glad for how long it took. And as I watched you walk out, I’d see that I’d earned your trust about that.

… This is the kind of content I hope to give in 2021—because I think I’d really, really like to write it. I think I’d like to learn to slow down, to be short and sharp. To promise dozens of small insights that will add up and reveal their value. It is my new experiment that I want to try, and I hope you’ll give me another chance at doing so.

And, of course, I’ll keep you abreast of what else I’m doing and writing. Ideally, this little space will be your first window into some thoughts that only become more lucid and valuable down the road. I’ve had lots of ideas lately, and wish I’d pulled the curtain back on a lot of them earlier. In fact, let me catch you up right now, with a great big thank you for sticking around and a meek but earnest see you very soon:

Writing Updates

January 2020: I published my poem "Credo" in Fathom Magazine. "A poet," says the Orthodox priest and poet Kaleeg Hainsworth, "must be someone who is devoted to the truth, to the seeing of things as they really are." I wrote this poem out of frustration, out of the sense that I lacked the kind of clarity Hainsworth describes and could only hope to grow into it.

June 2020. Giorgio Agamben is my favorite living philosopher, and features heavily in my dissertation. I don't agree with him on everything, and his response to the COVID-19 pandemic was especially polarizing. This summer, Church Life Journal asked me to write up some thoughts, and the result was "Agamben and Francis After the Quarantine". Here, I lay out Agamben's project as clearly as I can, and suggest that his hopes for humanity are best accomplished by the very religious tradition he rejects. This piece was later translated into Chinese, a major first for me, and evidence that I can still make meaningful academic contributions even if I'm not in the academy anymore.

August 2020. The end of the summer marked my biggest writing milestone: my first pro-rated sale, a very short story called "Bargaining", to Short Edition's Short Circuit #3. In this bittersweet romance, the narrator has a hard time distinguishing between the person he pines for and his own idealized past. This story was a major lesson in cleaving to my own standards, and enjoying the different interpretations such a short piece can evoke.

October 2020. "The Adolescent", in Nope 2, marks my third appearance in TL;DR Press's increasingly excellent lineup of creative writing anthologies, as well as my third stint as an editor with the charity press. This story, whose tone one friend compared to Matheson's I Am Legend, looks at how the line between man and monster blurs when the walking dead start hiding the fact that they're regaining sentience.

January 2021. I reviewed An Altar in the Wilderness for Legible. Fr. Kaleeg Hainsworth eschews mystical authority and approaches readers with radical vulnerability. Poet, priest, and father, he speaks of finding God in nature despite a story of failure, divorce, and precarity. Hainsworth invites us into the wilderness to heal in the ways he has healed.

Aha! He's back in the saddle. Can't wait to dig into what you've got coming. I'm so steeped in marketing/professional/content creation thinking I'll need the humanities dose 🚀