Of Time and Third Avenue

Alfred Bester on plot, pacing, and the magic bullet for making all your dreams come true.

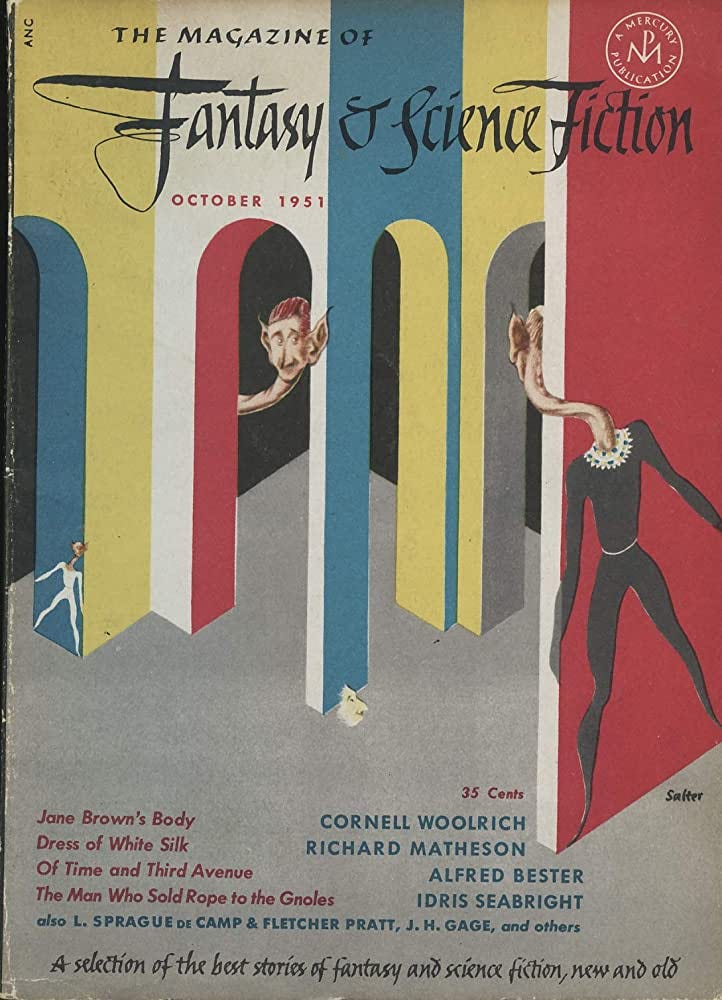

There’s a story I’m regularly drawn back to, from the Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction’s tenth issue. In Alfred Bester’s “Of Time and Third Avenue”, published in 1951, the enigmatic Boyne (who, as we know from the first paragraph, wears clothes that “squeak”) tries to talk a bewildered young Mr. Knight out of his most valuable possession: an almanac from the year 1990.

I appreciated

’s recent admission of being “thinly read”, especially as I am probably one degree worse than him. I read slowly, deeply, though not always with retention, and—kicker of kickers—I can probably count on one hand the number of books I’ve re-read in my life. So the very fact that I come back to this story is telling for me and worth thinking about.It’s not the premise that pulls me in, I don’t think. As time travel stories go, “Third Avenue” is simple, dry and hilarious. Boyne is full of phrases that are anachronistic in the wrong direction, and so he has to keep correcting himself so that Knight can understand him. (Where Boyne comes from—or rather when—the word “hour” has been replaced by “chronos”, which leads to their first misunderstanding.)

Complicating Boyne’s predicament further is that Knight does not know he’s picked up an oopart, and it’s imperative (for reasons unstated) that he not actually cognize his mistake. So Boyne is in the rough spot of informing Knight that his almanac is a dangerous snarl in time and space, but he insists that Knight can’t actually look at the thing or else an already disastrous situation will get worse. The be-all-end-all of chronological catastrophe would, of course, occur if Knight consulted the almanac and learned information that isn’t supposed to be available for another 40 years.

Even typing this makes me realize how loosely Bester’s rules of time travel actually hang together, but in this little story (~3000 words?) they really aren’t the point. The fun of the story comes from Boyne’s back-and-forth with Knight, and the arguments the former man uses to try and get the latter to give up an enormous advantage towards wealth and power.

Which raises another reason why this story is so interesting to me: it’s a well known rule of fiction that stories, to be experienced as such, require movement and change:

“Scenes” link up the different phases of a story, but they are not small stories unto themselves. Scenes cannot capture the dramatic movement through time and space from one status quo to another, or the emotional renegotiation that happens in a denouement. This is what makes flash fiction, especially, so damn hard to write, because the main things that distinguish flash fiction as fiction as opposed to prose poetry are exactly those two things: change and movement, credibly rendered in under 1500 words. (Just ask

over at .)So it’s vexing that a story like “Time and Third Avenue” appears to have neither movement, nor change, and yet it reads as a fully fun and credible narrative experience. All of its action takes place in an out-of-the-way booth in a New York pub. There is a bit of a cheeky reveal by the end, but it’s hard to say that something has changed in a consequential way. Certainly, when you’re looking for those elements on a second reading, you’ll be tempted to throw up your hands and say, “Zounds! Not here! Bester’s bested us all and written a story without a story!” It’s on maybe a third or fourth reading that you realize the movement and the change have subtly but delightfully been there all along.

First, Bester fills a rather composed scene with urgency to make it feel alive. The waiter moves quickly in and out of the room while Boyne chats with Knight’s bewildered date, Jane:

“Gingerbeer,” answered Boyne gallantly as Macy arrived, deposited bottles and glasses, and departed in haste.

“You couldn’t know we were coming here,” Jane said. “We didn’t know ourselves…until a few minutes ago.”

“Sorry to contradict, Miss Clinton,” Boyne smiled. “The probability of your arrival at Longitude 73-58-15 Latitude 40-45-20 was 99.9807 percent. No one can escape four significant figures.”

Boyne has an air of inevitability here that ratchets up the strangeness of the situation. He has something to say, and because he’s done the math neither Knight nor Jane can get away from him. The couple—and so we, the audience—must here him out. With the capture complete, Boyne explains the situation to Knight, who is more than a little skeptical:

“What the hell are you talking about?” Knight exclaimed.

“One bound volume consisting of collected facts and statistics.”

“The Almanac?”

“The Almanac.”

“What about it?”

“You intended to purchase a 1950 Almanac.”

“I bought the ‘50 Almanac.”

“You did not!” Boyne blazed. “You bought the almanac for 1990.”

“What?”

By using dialogue tags sparingly and choosing some downright audacious ones for effect (Boyne does not “say,” be “blazes”), Bester simulates a snappy, red-hot conversation between an impatient chrononaut and his disbelieving mark. The dialogue has already launched out of the gate and made it once around the track before we even realize what’s happened.

This is good, because Bester wants to take us places. And without the “blazing” of the prior page, those places might otherwise feel as stuffy and banal as a freshman philosophy classroom, as Knight realizes his out-of-place Almanac could help him tell the future:

“That’s the idea,” Knight said. “That’s for me.”

“You really think so?”

“I know so. Money in my pocket. The world in my pocket.”

With the cat out of the bag, Boyne must now talk the young Knight down from his power trip. This is the major conflict of the story, and we’d expect it to be suitably high stakes and dramatic. So Boyne makes his appeal…

“Excuse me,” Boyne said keenly, “but you are only repeating the drams of childhood. You want wealth. Yes. But only won through endeavor…your own endeavor. There is no joy in success as an unearned gift. There is nothing but guilt and unhappiness. You are aware of this already.”

“I disagree,” Knight said.

“Do you? Then why do you work? Why not steal? Rob? Burgle? Cheat others of their money to fill your own pockets?”

“But I—” Knight began, and then stopped.

“The point is well taken, eh?” Boyne waved his hand impatiently. “No, Mr. Knight. Seek a mature argument. You are too ambitious and healthy to wish to steal success.”

It is almost a letdown, how Boyne simply and transparently appeals to Knight’s sense of fairness. Knight is a good-old-boy, a straight shooter. Boyne is gambling on the fact that Knight’s own inherent gentlemanliness will save the future from devouring itself. That Knight’s protests are ultimately empty, his temptations ultimately conquerable. It’s downright wholesome in a way that’s honestly kind of refreshing.

But it’s also, let’s be real, a little boring. If the story ended here, with Knight admitting, “You know what, yeah, I am too much of a boy scout for this,” it would be disappointing. Knight wouldn’t have sacrificed anything, or learned very much about himself in the process. We as readers wouldn’t have the satisfaction of watching someone change.

Now that I’ve said all this, you might expect that Bester ramps up the tension in the last few pages and takes the story somewhere completely unexpected. This really isn’t the case. Knight quietly gives up the Almanac, and Boyne leaves him with a pricelessly anachronistic token as thanks. How does Bester make it satisfying?

For almost a full minute the young couple stared at [Boyne’s] bleached white face with its deadly eyes. The half smile left Knight’s lips, and Jane shuddered involuntarily. There was chill and dismay in the backroom.

“My God!” Knight glanced helplessly at Jane. “This can’t be happening. He’s got me believing. You?”

Jane nodded jerkily.

“What should we do? If everything he says is true we can refuse and live happily ever after.”

“No,” Jane said in a choked voice. “There may be money and success in that book, but there’s divorce and death too. Give him the book.”

“Take it,” Knight said faintly.

The day is saved by Knight being a good man, but not quite in the way Boyne anticipates. Boyne expected Knight to be a sporting gentleman who wanted to come by his success honestly. He is those things, of course. But it turns out he’s also a family man, someone for whom the risks of “divorce and death” are too much to bear. Knight doesn’t learn this about himself until Jane fully confronts him with those possibilities. In the end, Knight saves the world—and secures his own relatively modest fortune—by listening to the woman at his shoulder.

There’s not much left for me to say here except that I kind of love that. It’s easy to feel like I’m constantly struggling with my own definitions of success, and seeking out the oracles that might point me towards it. With that kind of race always blazing around in my head, I’ve realized it’s nice to have a story like this that’s not only instructive to me as a writer, but teaches me about my craft while also pointing me back to the good things I already have.

It’s certainly worth rereading a few more times for that.

Wow, this was great, and your review had the movement of change as well as we see you expand your understanding of yourself even further. Well done!