When I started lifting weights, I couldn’t rack up gains fast enough.

(God I feel slimy after saying that. Oof. Anyway.)

Of course, no amount of gain could catch me up to my friend Josh, who’d started well before I did and was also way more serious. While I was proud of crossing the 300 pound mark on my dead-lifts one fall evening in 2019, Josh immediately took the wind out of me by sending me a video of him squatting something over 500.

Comparison is the thief of joy, of course—a lesson I often cite but perpetually fail to learn. So I tried to focus on myself, and on getting 1% better every day.

That lasted until a former Olympian stopped me one day and informed me that if I didn’t shape up my power-clean form, I was probably scant weeks away from a pair of chicken legs—not because they’d be underworked, but because my knees would blow backwards.

This generous man worked with me until he was satisfied that I wouldn’t kill myself, and after that my concern with raw numbers took a back seat to making sure that, whatever numbers I was pushing, I was doing them right.

It all payed off when, during a gym-stint in my new town, an older man circled my rack while I did squats, shook my hand when I’d finished and said, “Good form. Well done.” (I’ve been too happy over the whole thing to think about how creepy it was; please don’t burst that bubble now.)

This little anecdote leads me directly into complaining about Stephen King’s advice on plot and why I think you should do (or try) something different.

The Perils of Plot

In his excellent book, On Writing (2000), Stephen King gives a bit of advice that has always hit me slantwise, unlike anything else in those pages:

I believe plotting and the spontaneity of real creation aren’t compatible… I want you to understand that my basic belief about the making of stories is that they pretty much make themselves. (163)

It’s not like King doesn’t justify his thoughts on plot. “For one,” he says, “our lives are largely plotless,” and to pretend that singular lives break out of this meandering, almost accidental formlessness is a discredit to the work of fiction. So good stories must preserve the carelessness of real life; they are not engineered, but discovered, the way a fossil would be:

No matter how good you are, no matter how much experience you have, it’s probably impossible to get the entire fossil our of the ground without a few breaks and losses. To get even most of it, the shovel must give way to more delicate tools… Plot is a far bigger tool, the writer’s jackhammer. You can liberate a fossil from hard ground with a jackhammer…but you know as well as I do that the jackhammer is going to break almost as much stuff as it liberates. (164)

I’ve read this book maybe four times now and I’ve always asked the same couple of questions right here: One, what exactly is “plot,” then? (Because Stephen you haven’t exactly defined your terms, here.) And two: when is the right time to use a jackhammer?

I think that King is talking about ready-made plots, the things we’ve learned to call “tropes” and cliches that amount to long-ranging games of MadLibs or paint-by-numbers. Spin a wheel and get a ready-made guide for all the things that are supposed to happen; you just need to provide the names.

In this sense, I think King is absolutely right. When plot is prescriptive, it is anti-creative and simply sets you up with a series of tasks you need to accomplish to write what someone thinks is a good story. But if he means to suggest that simply working ahead lands you in the same traps, then I have to beg to differ. We can all appreciate that King is an avowed and unapologetic “Pantser” to the core, and I really don’t think he means to throw everyone with a different process under one of those trucks from “Big Driver.” But as a convert and catechumen in the ways of Plotting, I feel the need to defend my faith.

(In fact, to go ahead and over-milk the religious metaphor: I find King’s statements on plot to be the writers’ version of, “Faith is just believing in something without evidence.” It really isn’t, though if I’m honest I see how you came to the conclusion, but it’s still so emphatically wrong that I’m not going to let you get away with it.)

Here’s my diagnosis: I think that King so ingrained and internalized the basics of storytelling from so early on that he finds it hard to remember what it’s like for the rest of us who feel we’re poking around in the dark sometimes. He encourages the racking on of weight, having forgotten what it was like to learn form in a kind of halting, unsteady way.

For those of us clutching our 15,000 word outlines, I want to come to our defense and say that King is wrong—but maybe not, finally, in the kind of total way we want him to be. Ultimately, I want to argue that playing with plot is a little like a white person dancing: it’s obvious when someone doesn’t have rhythm, no matter how well they know the steps… But unless you know some steps to practice, how will you ever find your rhythm? Your jazz? Your—and let’s get real literary here for a second—your inscape?

Form and Freestyling

I’m going to talk about poetry for a second because I think it will help—and also because I’m kind of over making too-fine distinctions in various “acts of creation.” We’re still talking about “telepathy,” as King calls it, and I think some poetic insights will help. These thoughts might start out a little “mystical,” in ways that’ll make a few of my fellow writers cringe, but I promise to bring it all to ground by the end.

Specifically, I want to suggest that fiction thinks about “plot” much the same way poetry things about “form”—i.e., the way a piece of writing lands on the page, becoming recognizable as a poem, a story, a novel that is trying to do a specific kind of work. Poetry boasts myriad forms like sonnets, villanelles, sestinas and more. Story-writing…doesn’t have all this. But its forms are still myriad—though we might call them “genres” or “tropes” or what have you. Whatever King wants to say about “plot,” his insistence on “story” means he can never get away from form, even if that’s what he was trying to do.

Even if we can’t define it in as granular a way as we could for poetry, form in fiction is too important to write off. And if we’re going to talk about it, I think we could do worse than deferring to the poet Denise Levertov, and her riffs on a concept she learned from Gerard Manley Hopkins. For both poets, there is a “rhythmic form [that] is peculiar to a particular poem”—a singular uniqueness and mode of existence that Hopkins calls a thing’s “inscape.” Levertov expands on the idea:

There is a form in all things (and in our experience) which the poet can discover and reveal… [Poetry] is a method of apperception, i.e., of recognizing what we perceive, and is based on an intuition of an order, a form beyond forms, in which forms partake, and of which [humanity’s] creative works are analogies, resemblances, natural allegories. Such poetry is exploratory. (“Some Notes on Organic Form,” 7)

Levertov isn’t using “inscape” to justify a kind of wibbly-wobbly free-formy commitment to free verse; she’s speaking as a committed formalist whose practice with form has given her unique insight into its plasticity and potency. She truly does believe that certain poems become their best selves when disciplined into a particular form; but she also believes that “discipline” results in discovering a poem’s singular form, one that ultimately stretches beyond the categorizations of sonnet or lyric or whatever. A poem may take the form of a sonnet, but a good sonnet becomes more than its form, and becomes something absolutely unique.

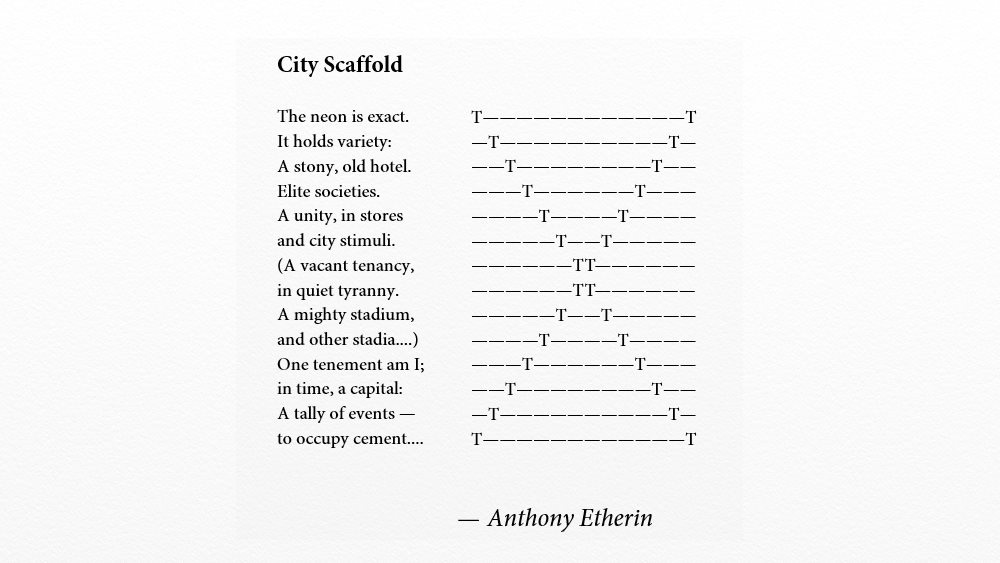

In fact, extreme constraints of form have resulted in some of the most creative, unique, and singular poems ever produced. The poet Anthony Etherin offers an incredible example in the form of his City Scaffold: “A sonnet of no fixed rhyme scheme, composed in iambic trimeter. Each line has exactly 14 letters. The poem's Ts are arranged such that they form a symmetrical, X-shaped scaffold.”

The same thing, I think, is true of story, perhaps on a more potent level. Sometimes, the “spontaneity of creation” occurs precisely when we constrain ourselves to a set of tropes we want to break or transform, locking ourselves into a set of narrative problems that can’t be solved simply by flying off the cuff and blitzing through chapters, the way King does.

Ultimately, I think King’s advice is meant to encourage new writers to privilege the specific over the general, to recognize that thinking in too broad of categories often leads us to forget or erase the small, spontaneous details that make life (and fiction) so interesting. But to get to where King is, slinging around his own advice, you need to develop a sense of intuition about story and form that you can draw on naturally—or, you can accelerate it through deliberate study. With the right attitude and goals in mind, tropes and generalizations can themselves become lenses for zeroing-in and focusing on inscapes: the things that make our stories unique, spontaneous, and special.

Practice Reps

For those of us who discovered and cultivated style before we did the same with story (*embarrassed ahem*), plot outlines and outlining in general can be a lifesaver. For some of us, story “beats” just don’t come as naturally as they do for others, and in order to get them to come naturally we need to look at them on a rubric of some kind.

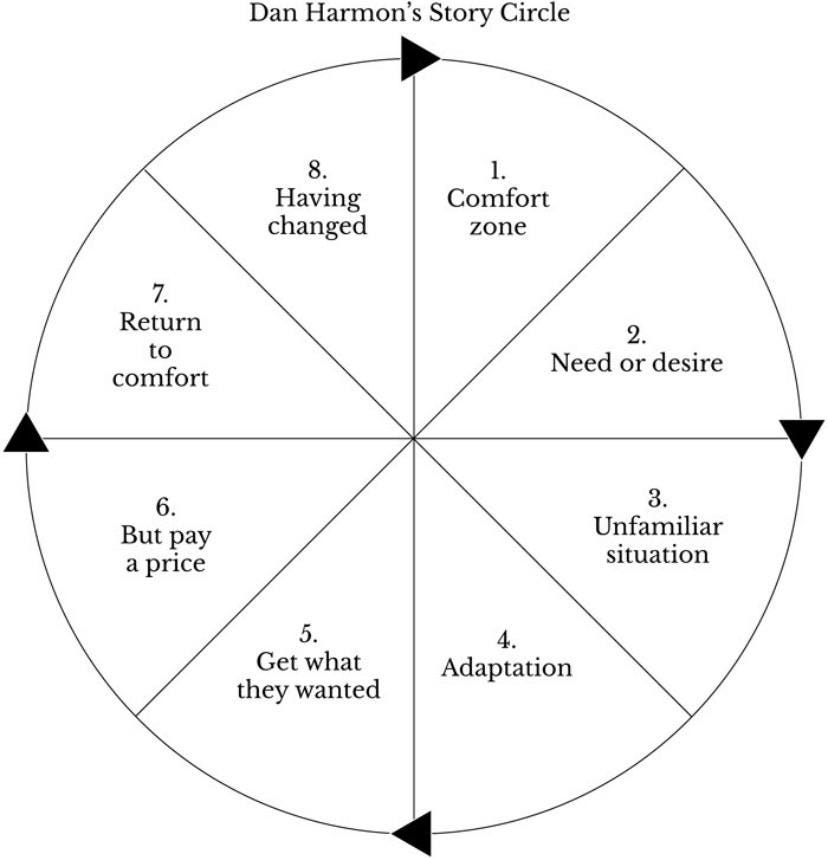

Anyone who knows me and my writing (or who has taken a creative writing course with me!) knows that I am a big fan of Dan Harmon’s Story Circle, but if you need a brush-up, you can read a great summary here.

At first glance, we might see in Harmon’s Circle an echo of the dreaded “Plot Wheel” that King warned us against, but let’s appreciate the differences here: Harmon isn’t telling us what to do, he’s not telling us which “plot points” we have to include to create a best-seller. His eight sections of the Circle are far too abstract for that. To go back to the weight-lifting metaphor, he’s not telling us how much weight to rack up on our stories but he is giving us a basic idea of how our stories should move when they carry that weight in order to avoid breaking in half.

While I could keep theorizing on this, I think an example will work far better. So let’s take King’s famous experiment in On Writing (you can find it as the top post of this forum here), but let’s do exactly the opposite of what he says. Let’s plot it. Specifically, let’s use Dan Harmon’s Story Circle and give it a basic plot outline. And let’s not even stop there; let’s try throwing things on the wheel and seeing what sticks:

In this exercise Dick is the protagonist—the unwitting stay-at-home dad… Or, you might decide that Jane is the protagonist, having been wrongly put away by her husband. And that doesn’t even get into telling the story from a flipped POV. Either way, we’ve got our status quo, our “Comfort Zone,” our "(1).

(2) “Need or Desire.” I find this point most important because thinking on this teaches me more about my characters than anything else. In this case, the obvious answer might be that Dick needs to stay alive, but that’s also kind of obvious, isn’t it? What if “staying alive” is secondary to something else? Making sure Little Nell is safe, for instance? Or what if Dick actually wants to reconcile more than he wants to save is skin? Whatever he says or does is going to be driven by our answer here, and that does doubly for Jane, whose motives might be all over the place. Do their desires conflict, or do they converge in an almost comedic way? If we learn their desires converge only after violence breaks out, then we have a tragedy on our hands…

Our “Unfamiliar Situation” (3) is pretty well established, but now we have to think about how these two will adapt during their encounters with one another (4). Will violence be a first resort? Again, that depends on what they want, and why. If Jane tries to talk Dick down first, then she certainly has reason to believe he’ll hear her out. This should also be reflected in how her needs and desires are understood in (2).

Now things get interesting. Up to this point, we’ve been playing with a pretty predictable build-up and set of questions. From here, all number of fresh hells can break loose as one—or both—of our characters get what (they think) they want (5). For the sake of experimenting, let’s assume that Dick manages to get away from Jane. Permanently. He kills her, I’m saying. This beat rhythms the story differently depending on where you place it. We could make a traditional thriller out of it: after a brief escape from Jane (5) during which Dick loses an eye (6), he must finally make his stand and kill his estranged wife in order to return his life to normal (7), even though he now lives with the knowledge that he killed his daughter’s mother (8). If we move those beats around, though, we completely change the story: what if Dick kills Jane at (6)? What if her death is the “heavy price” he must pay? This would be an appropriate rhythm for a tragic tale of reconciliation gone awry. If it all happens right at (5), we still have something like half a story left to go—and we also have the implication (maybe even the expectation) that Dick got what he wanted when he killed Jane. If Dick is not the simple victim we’ve imagined him to be thus far, what price will he ultimately pay for showing his true colors (6)?

Now that we’ve done this, try and feel the “beat” of the story… What do you see? How does it feel? Do certain elements of the story “fit” better at certain parts of the wheel? Do you see how allowing a stage of the story to “beat” its rhythm in a different place changes the story completely, demands different things of it?

Jazz Still Needs Drummers

Hey hey, Speedy Jones is a damn beast.

With all this talk of “rhythm,” maybe it’s smart to think of the “Story Circle” as a drum. We’ve tanned the hide and built the frame, but now we’re stretching the skin from edge to edge and see how it thumps. That’s all good “plotting” is I think: thumping on your drum, tuning your instrument until it sounds pleasant, until it bounces and bruises in the ways you like, and then fastening it all up so you can play the whole song without worry that your improvisations and your jazzy moments will all sound off-key.

This, I think, is the real magic of plotting: not to impose a rigid structure, but to give a story room to breath and to express its rhythm before you’ve gotten too deep into the weeds. Plotting does not have to destroy a story’s singularity, the way King seems to imply—but he’s right to say that it’s a dangerous exercise and, just like lifting weights, there’s an art to stressing and stretching a story in order to help it grow and breathe and be itself. The trick, I think—to navigating a happy medium between King’s advice and and the real life of writing—is to remember that the purpose of an outline is to stretch your story. Once you get the corners in tight, you see what else it’s capable of doing. Get it real thin, almost translucent, so you can see through it. But don’t stretch it so hard is snaps—the Story Circle is not a torture wheel. If we treat it that way, then King is right to tell us off.

Point is, satisfying stories all have loads to bear; all load-bearing requires a form of some kind. That form comes more naturally to some of us than others. But I am very confident that those who deliberately practice it aren’t wasting a single moment of effort.