Elden Ring, the Omen King, and the Shadow of Death

"He loved not in return, for he was never loved. But nevertheless, love he did."

This post responds to a monthly prompt from the

Symposium. This month’s theme is “Death”. I was—at the grim urging of and — originally supposed to contribute a piece of fiction that somehow worked “necrophilia” into it. I did not fail in this; rather I succeeded so spectacularly (or, like, I’m getting there) that I’ve decided to selfishly withhold the story and try to place it with a magazine instead. Trilety, at least, forgives me, so in the meantime I return to some thoughts about what is arguably the Greatest Video Game of All Time and why I can’t bring myself to finish it. I hope you enjoy.I first met the Omen King on Stormhill. He called himself Margit, then, and I called myself a wretch. We both called me “Tarnished” — meaning, in different ways, that I might have been glorious once. He mocked me for my “meager flame, emboldened by ambition.” I wondered that he saw boldness in me at all: white-knuckling my sword in the shadow of his horned crown; quailing like a rabbit for cover beneath his maul and rod.

He killed me. Again and again he killed me, until death became meaningless.

And then, one day, I killed him.

And I have mourned him ever since.

The “boss” is an odd bit of video game parlance, a puzzle to non-players and a totally unquestioned feature to those of us who grew up with a controller in our hands. A "boss" is any unique, cinematic enemy that puts the player through the wringer, forcing you to master the skills required for the next stage of the game.

Naturally the first boss is a challenging but manageable skill gate.

Unless you're Elden Ring's Margit the Fell Omen, in which case you still stump 30% of the 10 million people who bought the game. Elden Ring’s action-heavy fantasy combat requires rhythm and impeccable reactions, and Margit is designed to frustrate both:

At From Software, director Hidetaka Miyazaki has made a name crafting video games that feel like work. Media theorist Espin Arseth has a $400 word for art like this. He calls it “ergodic”: art that requires real effort to consume.

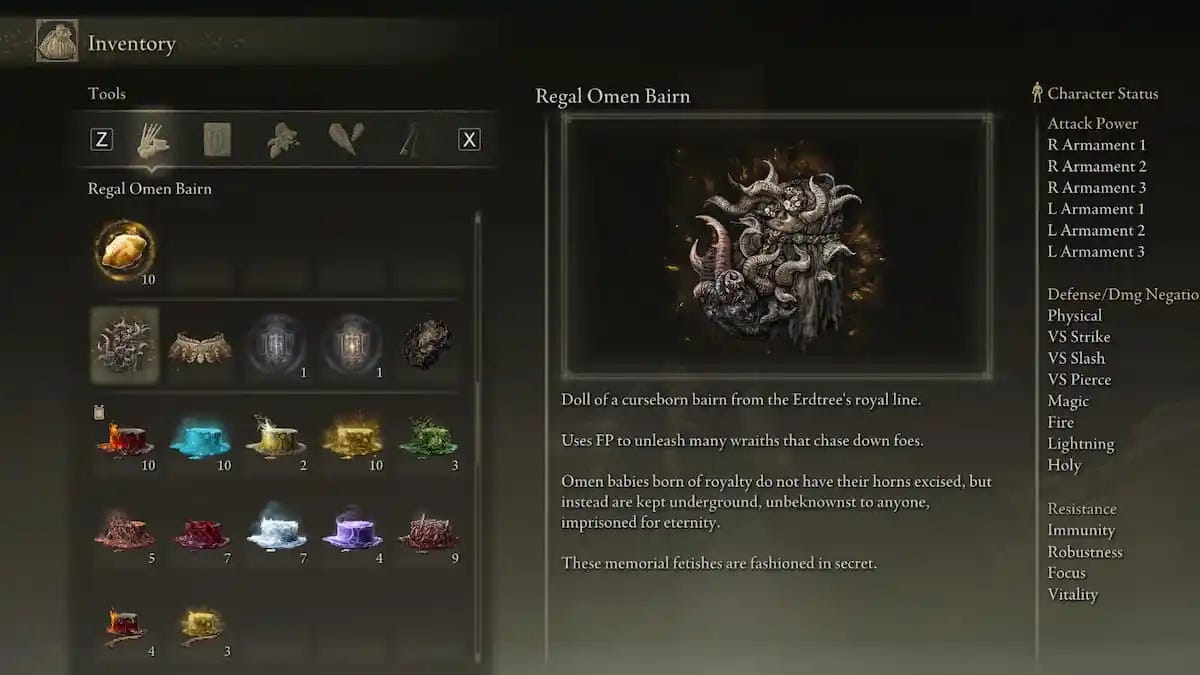

You could say that video games have always been the original form of ergodic art.1 The narrative exists behind skill-locked gates, and unless you can progress through the game’s challenges, the story's twists and resolution remain mysteries. FromSoft games crank this to 11, requiring tremendous skill and commitment to the world’s “text”. It’s impossible to know what’s going on without taking risks and delving into danger, seeking obscure items and lore—which is itself usually contained in item descriptions:

Your reward for this effort is, more often than not, the softening of a horrific world into something more tragic. Savage monsters and imposing demigods suddenly appear pitiful against the epic histories these games reveal one obscure piece at a time. You start to feel that you—player and character—are participating in the inevitable decay of something that was once beautiful.

Because these games sometimes lack context and clear stakes for their brutality, the sense of being an anti-hero can become dizzyingly uncomfortable. Enemies may be present, setting you on edge, but won’t attack unless—or even if—you attack first. Denizens of Elden Ring’s Siophra River may ignore you, dancing before primal fires lit for their dead gods. Servants in Leyndell Capitol will sit against walls and stare into the middle distance, basking in the golden rays of the Erdtree: the one beautiful sight left to their deathless eyes after their home has fallen apart.

FromSoft games are sneaky, punishing affairs, and in those few moments when they’re not keeping you on your toes, the anticipation of violence confronts you with your own violence’s complexity and the ways it tarnishes the world's strange glory. I can’t stress this enough: Elden Ring treats you like a hero in order to drive home the fact that you’re not, and imbibing this lesson has been one of my most emotionally demanding experiences in recent memory.

But if I’m going to better explain this, I need to tell you about the tragedy of the Omen King.

If you want an even deeper dive into Elden Ring’s story, watch the above video from the incomparable VaatiVidya.

Your ostensive goal in Elden Ring is straightforward fantasy fare: a warrior returned from death by the Greater Will, you must punish the hubris of Marika, queen of the realm, and restore the Elden Ring, which is something like the divine DNA of reality.

On your journey, you learn the Greater Will may not be entirely truthful, and that its preferred configuration of the Elden Ring—the Golden Order—may not be best for the world. Follow any but the most obvious narrative path, and you soon find yourself on a quest to kill God.

Before that, though, you need to kill God’s biggest fan.

Morgott is one of the last surviving children of Queen Marika. In ages past, his horns and deformities would have marked him as divine. But the Greater Will, in its rivalry with the old magic of the Lands Between, sovereignly declared Morgott’s blessing to be a curse. He was shackled underground, where his existence could not sully the purity of the Golden Order.2

Yet Morgott still loved his God, the Order, and his family. He accepted his “wrongness,” and tried to redeem himself by worshiping that which named him a monster:

Though born one of the graceless Omen, Morgott took it upon himself to become the Erdtree's protector. He loved not in return, for he was never loved, but nevertheless, love it he did. — Remembrance of the Omen King

When his mother shattered the Elden Ring, no one jumped more zealously into the fray to defend the throne against usurpers. And after these wars nearly destroyed civilization, Morgott established himself as de facto ruler of the Lands Between, and high priest of the Greater Will.

As the Veiled King, Morgott still serves those who abandoned him. He is a weary, hermetic figure, watching over a throne the Greater Will will not permit him to take.

At the beginning of the game, Morgott confronts the player under the alias Margit. He is, for most, Elden Ring's first major boss fight, testing the player-character’s resolve and warning them off their quest. A long journey later, when the player confronts Morgott in Leyndell’s throne room, the King strikes with the full force of righteousness and prodigious love.3 The whole game has been building to a climactic rematch between an old Order, struggling to survive, and the fragile promise of a new one. Though he’s far from the last boss, this second fight with Morgott is one of the hardest and most technically demanding of the entire game:

… At least, that’s how it’s supposed to be.

In a game like Elden Ring, where you’re given free reign to explore the world and prepare for challenges, you can face some of the toughest enemies with more power and resources than the game’s design intends. And if you're like me, you get so anxious about those fights that you push an overpowered play style to the limit.

So players report wildly different levels of struggle with Morgott, depending on how they play. Some, like me, found him easy. A pushover, a speed bump. A total anti-climax.

Normally, this might ruin the pace and immersion of a smoothly-told story, but as a master of the medium Miyazaki anticipates that some players may over-prepare for this battle. In a bold move, he chooses not to create any branching paths, but instead crafts a narrative that feels very different depending on your style, making the deeper meaning of the story a matter of audience reception.4 Our choices indelibly impact how we experience Elden Ring’s story—and how I’ve personally thought about story itself in the aftermath.

You see, I literally cannot finish Elden Ring because of the regret I feel from over-leveling and steamrolling Morgott. It has nothing to do with denying myself a challenge. It's that, in doing so, I cut short the story this character was telling before it had a chance to mean anything. The abruptness of his death underscores and emboldens the tragedy of his life.5

Death is the fulcrum of all our ideas about drama. We want our stories to be filled with “good” deaths or “earned” deaths. Deaths that mean something. Deaths where heroes and villains alike go out fighting. In the story of Elden Ring, no one deserves a better death than the Omen King.6

By denying him that, I feel I’ve ruined something. Tarnished the story. There’s a lump in my throat that’s sat there for a year, because my power-mongering path ended in a terrifying reminder: that death is no respecter of the dramatic patterns we frame around it.

In real life, death does not wait for peaks or troughs in the arcs of our stories. It strikes whenever it wants. We say it gives meaning to our lives by making them bounded, finite, but death does not obey the dramatic contours of the meaning it supposedly makes possible. It crashes through them, mangles them, laughs at them.

Elden Ring has a way of making us feel responsible for that. It deconstructs our ideas of heroism and takes the measures of our consciences. I am, for example, more aware of myself as an heir of colonialism, because my encounter with Morgott confronted me, in a fresh veil, with questions that are far too easy for me to stop asking:

How might it feel to be this horned “monster”, fighting to tell his own story, only to have it abruptly ended by someone else?

Have I become desensitized to my own complicity in others’ broken stories?

This isn’t an accident, either; Elden Ring is full of historical and literary references to colonial and imperial violence.7 Beneath them all lies a churning reminder of what violence—even “heroic” violence—actually is: the brutal interruption of life that no drama can redeem.

This brings us back to Arseth and the “ergodic”. In my opinion, the best art—not the most “genius”, the most “authentic” but the best—invites effort from the consumer. We don’t have to accept this invitation, of course, but when we do, when we consent, we place ourselves at risk. We encounter a demand that, when we rise to it, changes us. Within this gap, this risk, artists like Miyazaki push the limits of their media and haunt us with things we tend to forget. Each of us has questions we could not ask without the accompaniment of the arts.

And thank God for that accompaniment, as it so often leads us through the valley of the shadow of death.

“Ergodic literature” that is not also interactive media has its own category, with Mark Z. Danielewski’s House of Leaves regularly leading example lists, with Doug Dorst’s S. not far behind. May I also recommend my friend Joe’s “Haunted Hotel Project”, or

's "2X21"?Why a true divinity would need to “ban” anything in order to maintain its purity is, of course, a rather absurd question from the moment you scratch at it. Elden Ring spends much of its subterranean story interrogating religious ideas like this, and the Greater Will’s need to remain “unsullied” through bans and scapegoats is some of the biggest evidence that it is far, far less than anything deserving the name “God”. See also Giorgio Agamben, Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life (1991).

Remember the game’s description of Morgott? “He loved not in return, for he was never loved, but nevertheless, love it he did”? I’m taken with how closely this phrasing mirrors Jorge Luis Borges’s poem “Baruch Spinoza”: “No one / Is granted such prodigious love as he; / The love that has no hope of being loved.”

In the poem, Borges describes the Portuguese-Jewish philosopher — one of the greatest minds of all time — “building God in a dark cup.” Spinoza’s most enduring and controversial idea was that God and Nature were one and the same. Elden Ring, too, contains many oblique references to Spinoza; one of the most enigmatic yet ultimately heroic characters in the game, Goldmask, is like Borges’s Spinoza, “[A] magician moved / [who] Carves out his God with fine geometry.” It’s an absolutely wild rabbit hole to fall down, and I must recommend that you fall.

Lest I give all credit to Miyazaki, many of you might be excited to learn that George R. R. Martin, author of A Song of Ice and Fire, contributed significantly to Elden Ring’s lore. The fact that Morgott is a twin, for instance, is most certainly part of Martin’s signature, as his story explores the cursed nature of twins in mythology and the tendency for one to be hyper-loyal to their society while the other becomes an ambitious usurper.

I haven’t even mentioned the fact that you can add further insult to injury during these fights by using “Morgott’s Shackle” — an item hidden in the vast world of Elden Ring — to immobilize Morgott with the very chains his mother used to bind him when he was born.

In fact, death is an ever-present trope in FromSoft games; most worlds that Miyazaki creates feature a curse of “deathlessness” that explains the player character coming back from death again and again. These mechanics all serve much deeper, considered meditations on the nature of death, the curse of perpetual life without change, and the perils of rejecting finitude as part of human meaning.

There’s much more I could—and want—to say on this topic. Specifically, Elden Ring’s many meditations on religion mirror commentaries made by Japanese author Shusaku Endo about Europe’s attempts to Christianize Japan. If you’d like me to write more on this topic, please let me know in the comments or in Chat.

Well done, friend! Like i said outside of the comments, you made me care about topics that rarely interest me, and then used them to build a full of library of solid thought and branching offshoots of thinking. Appreciated the House of Leaves footnote as well las all the references little known to me!

This is some of the best writing about video games I've seen.